Welcome to the concluding part 4 of Poetic Traditions of Compassion and Creative Maladjustment. For the previous podcast episodes of this series featuring discussions on Martin Luther King, Jr., Jalal al-Din Rumi, and Gwendolyn Brooks, please visit the Flight of the Silver Skylark on Spotify. Part 4 begins now:

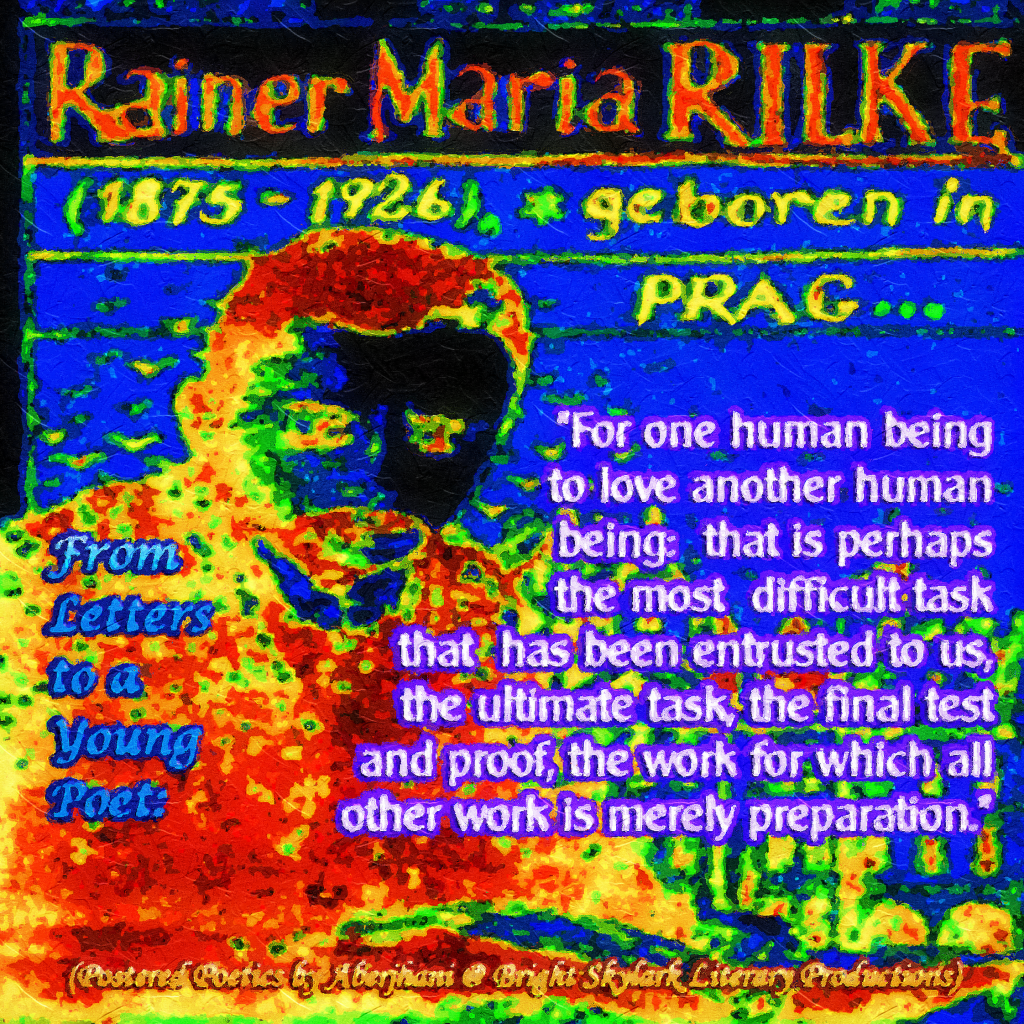

Quote: For one human being to love another human being: that is perhaps the most difficult task that has been entrusted to us, the ultimate task, the final test and proof, the work for which all other work is merely preparation. (From Letters to a Young Poet.)

Anyone proposing an assessment of the Prague-born author Rainer Maria Rilke’s (1875-1926) life, based on the most obvious external aspects of it in 1902, would find reasons to believe the then 27-year-old was settling happily into traditional patterns of career-growth and domestic comfort. He had married the sculptress Clara Westhoff (1878-1954) the year before and become a father to their daughter Ruth. The military-school years he considered the most painful of his life were long behind him. He had already published several acclaimed volumes of poetry, staged plays, and received a commission to write a book on the renowned sculptor: Auguste Rodin (1840-1917).

But these surface elements reveal only pieces of a much larger picture.

The difficulty stemmed from Rilke’s attempts to reconcile expectations society placed upon him as a man responsible to it–– with a powerful individual need to express innate impulses as a creative artist and spiritual seeker. Individuals in the United States, protesting the sting of budget cuts to funds for education and the cultural arts in 2017, could likely empathize with him in this dilemma. For them, as for Rilke, it boiled down to a matter of assigning recognition and value to specific qualities and activities.

A Self-styled Form of Creative Maladjustment

From his time as a youth, the future poet had attempted to honor family traditions by pursuing an education that would prepare him for a military or business career. The pull to pursue literature intertwined with an intense spiritual disposition proved stronger.

Through both his life and his works, he staged against repressive social and political conventions a quiet revolt informed by extensive travel, the cultivation of expanded knowledge, and a loving concern for humanity. All of this–even though the actual phrase would not be coined by Martin Luther King, Jr., until almost seven decades later–amounted to a self-styled form of creative maladjustment. As translator Stephen Mitchell saw it:

He required an enormous amount of space around himself; how much, he only began to understand after he was married. He both loved and feared solitude, he often wanted to escape from it, but it was the necessary condition for his poetry. The monk and the lover inside him, each a powerful and conflicting presence, were never able to merge…

(from Letters to a Young Poet, Random House Vintage Books, 1986, page xiii)

It was an odd kind of existential paradox: in order for the poet to give the best of himself to the world he had to maintain a certain psychic distance from it. Yet this need for solitude and distance did not prevent him from setting his inclinations aside early in 1903. That was when he received, from one Franz Xaver Kappus, copies of poems and a letter asking for advice on writing.

This Process of Turning Inward

Kappus was then a student at the Military Academy of Wiener Neustadt. There, he had befriended a school chaplain who knew Rilke when he was a student at another branch of the school. This connection via the chaplain, as well as Kappus’ position as a developing poet in a military environment, stimulated an immediate sense of empathy and recognition in Rilke.

Consequently, he began a correspondence that would last five years. During that period, he avoided glorifying romantic notions about what it meant to be a poet, and, from the very beginning, suggested Kappus should not be afraid to abandon the idea if he believed he could live without writing:

To feel that one could live without writing is enough indication that, in fact, one should not. Even then this process of turning inward, upon which I beg you to embark, will not have been in vain. Your life will no doubt from then on find its own paths. That they will be good ones and rich and expansive—that I wish for you more than I can say.”

(Rilke, The First Letter.)

Rainer Maria Rilke basically became Kappus’ long-distance mentor on various life issues. These ranged from: creative aesthetics and the need for individual solitude to health, sexuality, relationships, the independence of women, poverty, and stages of maturation.

The depth of his compassion toward the student may be seen in the fact that he often wrote the letters while traveling. They were therefore sent from a number of small towns in Italy and Sweden as well as from Rome and Paris. In this way, he carried Kappus with him. By doing so, he exemplified one of the most powerful classic interpretations of compassion: as opposed to simply expressing sorrow for any pain he might be experiencing, the poet helped him bear and eventually release it. At the same time, he confessed to struggling in his own life:

Don’t think that the person who is trying to comfort you now lives untroubled among the simple and quiet words that sometimes give you pleasure. His life has much trouble and sadness, and remains far behind yours. If it were otherwise, he would never have been able to find those words. (From Letters, page 97.)

Embodying the Poetic Tradition of Compassion

Like the other poets in this series, Jalal al-Din Rumi and Gwendolyn Brooks, Rilke in his writings does not dwell on the word compassion per se. He strives to embody it, often apologizing for taking a long time to respond to letters and frequently assuring the cadet that he meditates frequently upon the questions posed in them. Above all, he stresses that he should do the following:

Find in yourself enough patience to endure and enough simplicity to have faith; that you may gain more and more confidence in what is difficult and in your solitude among other people. And as for the rest, let life happen to you.

(From Letters to a Young Poet, page 101.)

It has been suggested that in this sustained correspondence–undertaken at a time when so much else weighed on him–– Rilke was writing to own younger self. Or: he was writing to show Kappus how to avoid the depression and failures he experienced in the same situation. In this way, he was doing unto another as he wished someone had done unto him.

Moreover, it is just as possible he may have been addressing an interior mirror image used to clarify the evolving values and objectives still giving shape to his life. In a sense, he and Kappus were walking miles in each other’s shoes as Rilke made his way toward these lines from “The Tenth Elegy” in Duino Elegies:

Someday, emerging at last from this terrifying vision,

may I burst into jubilant praise to assenting Angels!

May not even one of the clear-struck keys of the heart

fail to respond through alighting on slack or doubtful

or rending strings! May inconspicuous Weeping

flower! How dear you will be to me then, you Nights

of Affliction!...

(from Duino Elegies, translated by J.B. Leishman and S. Spender, W.W. Norton Publishing, 1939, page 79.)

Achieving a Functional Synthesis

By the time of the concluding letter, dated “the day after Christmas, 1908,” the military cadet had reached a point where he did not feel a conflict between his call to military service and his desire to become a writer. Each, as it turned out, helped enhance his ability to do the other well.

While writing may have helped make Kappus more critically discerning when confronting sensitive military issues over the next fifteen years, the military helped him develop the kind of discipline later required to sustain his career as a journalist, novelist, and screenwriter. He might not have achieved such a functional synthesis had it not been for Rilke’s dedicated compassion.

Just as importantly (if not more so) since its first German publication in 1929 and subsequent English publication in 1934, their published correspondence has continued to inspire countless readers–– poets and non-poets alike. It has guided them toward a willingness to address complex issues with deep mindful consideration.

Instead of allowing fear or hate to take over their hearts and dictate their actions, they have the documented example of what it means to engage agonizing difficulties with shared healing resolve. They have the powerful practice of compassion committed to sustaining life, and a courageous kind of creative maladjustment capable of simultaneously dismantling tyranny and constructing more perfectly-humane unions.

Program text for this podcast series was written by Ah Bear Zhah Knee (which is spelled: A-b-e-r-j-h-a-n-i)

author of The River of Winged Dreams

and Greeting Flannery O’Connor at the Back Door of My Mind

Rainer Maria Rilke blog post quotation artwork courtesy of Bright Skylark Literary Productions

You can learn more about author and artist Aberjhani at: https://www.author-poet-aberjhani.info/ .

Leave a reply to Skylark Aberjhani Cancel reply